UjENA FIT Club 100 Interesting Running Articles

Best Road Races and the UjENA FIT Club is publishing 100 articles about races, training, diet, shoes and coaching. If you would like to contribute to this feature, send an email to Bob Anderson at bob@ujena.com . We are looking for cutting edge material.

Click here to read all Running Articles

Posted Wednesday, February 11th, 2015

By David Prokop Pleasanton, Calif., may be a quiet, relaxed community across the bay from San Francisco, but where Double... Read Article

Posted Monday, September 15th, 2014

Peter Mullin has taken Double Racing® by storm. He broke the 60-64 age group world record in the first Double... Read Article

Posted Monday, September 22nd, 2014

by David Prokop (Editor Best Road Races) Photo: Double 15k top three Double Racing® is a new sport for... Read Article

Posted Sunday, May 11th, 2014

By David Prokop, editor Best Road Races The world’s most unusual race met the world’s most beautiful place, in the... Read Article

George Hirsch talks about Fred

Wednesday, February 15th, 2012

The Man Who Made the Marathon

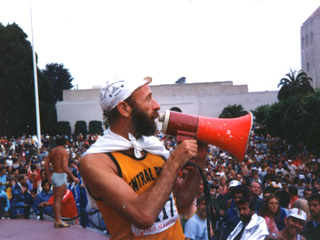

by George Hirsch If Fred Lebow, founder of the New York City Marathon, could see the 43,000 runners crowding together on the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge on Sunday morning, he would surely allow himself a slight smile. He would not be satisfied, however. He would want to see even more. Lebow was a dreamer and a schemer who combined a deep passion for running with a genius for promotion. Without him, marathoning in New York and around the world would never have reached its current mass appeal. In the late 1960s when I began running in and around New York City, few others were doing so. The city’s rare races were held on the streets of the Bronx, outside Yankee Stadium. I joined because, while working 50- to 60-hour weeks to start New York magazine, I needed to shed a few pounds. I soon met Lebow, who was making good money doing knockoffs in the garment district and thought that running might help his tennis game. We formed a close 25-year friendship that spanned successes, failures and dozens of trips to other cities and countries. Even though Lebow was a driven, irrepressible man, I could hardly have imagined how much running would change his life. Or, more important, how he would change running. Lebow gave up tennis and began running everywhere at every opportunity. He was not particularly fast, but it suited his spartan lifestyle. With no hobbies, serious interests, romantic attachments and an always-empty refrigerator, he was free to pursue his new obsession at any time of day or night. Before long, he agreed to take on the unpaid position of president of the New York Road Runners Club. In 1970, with money from his own pocket for soft drinks, safety pins and cheap watches for the winners, Lebow organized the first New York City Marathon, a four-loop race in Central Park. The event was underwhelming, with 127 starters and only 55 finishers who undoubtedly outnumbered the spectators. Nonetheless, Lebow was determined to build on it. The marathon grew over the next few years, but almost no one noticed. With the 1976 bicentennial approaching, an iconoclastic civil servant named George Spitz hatched the idea of a celebratory five-borough marathon. Lebow initially rejected the idea, calling it unfeasible. But Spitz persisted, and Lebow eventually embraced the five-borough marathon. Still a part-time volunteer, he threw all his energy and know-how into the race, the biggest challenge of his career.

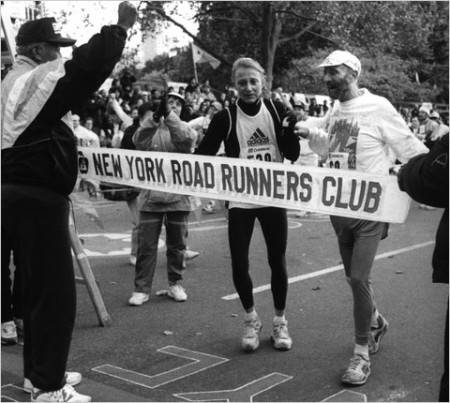

Photo: Grete Waitz and Fred Lebow at the 1992 New York City Marathon, when Fred was fighting brain cancer. The city had agreed to only a one-year commitment, so anything short of total success could have ended it all. Lebow massaged city agencies and politicians, fought over myriad details, attended endless meetings and worked the press with his lovable bravado. He lined up several sponsors, including my New Times magazine (for $5,000), and persuaded the American marathon stars Frank Shorter and Bill Rodgers to enter. Shorter accepted, he said, because “if they were going to close down New York for a marathon, I had to see it.” The only prerace news conference took place outside Tavern on the Green, with not even coffee and bagels for the few reporters who showed up. Comments and Feedback

|

,,,,, |

Lebow courted the news media with gamesmanship and chutzpah. One day he told me he was going to announce a $1 million bonus to anyone running New York in under two hours. I protested that this was a ridiculous, impossible time, at least in our lifetimes, and New York was not even a fast course. “You know that and I know that,” he said. “But one million dollars makes a great headline, and the public won’t take us seriously if this is just an amateur sport.” Lebow got his headlines, and simply tuned out the ridicule from the purists. In 1983, Lebow and I were invited to an audience with the pope at the Vatican. The pope praised the marathon as an event known throughout the world. Afterward, Lebow told me that he had called in the story. “It should get good press tomorrow,” he said, a twinkle in his eye.

But when it came to his own running, Lebow abided by a strict honor code. He once told a reporter: “I feel running is the oasis in life, the one area unlike business or relationships where one does not cheat or exaggerate. I will never write in my log that I ran a mile more than I really did. Running is my area of total honesty.” Fred loved women, or “vimmen,” as he called them in his heavy Transylvanian accent. He grew up in Arad, Romania, in a large orthodox Jewish family that fled the town after World War II. But his all-consuming devotion to running left little room for a real commitment. Lebow once fell hard for a lovely nonrunner, and moved in with her. The relationship came unglued on a New Year’s Eve. She had accepted an invitation for them to attend a formal dinner; Lebow, having reviewed his training diary for the year, realized he was 19 miles short of his goal, 2,500 miles. He headed out into the sleet and snow, circling Central Park for several hours. When he returned to the apartment, he found all his belongings neatly stacked in the hallway with a farewell note pinned to them.

Two years later, the cancer returned, and on Oct. 9, 1994, Fred Lebow died at 62. Four weeks later, his beloved marathon was turned into a moving tribute to the man who had given New York City and running its finest day. |

Copyright 2025 UjENA Swimwear · Site Map · Feedback · Tell A Friend · Nominate a Race

Leaderboard · UjENA 5K · Double Road Race · UjENA Jam · UjENA Network

The race went off seamlessly, with Rodgers beating Shorter for the first of his four consecutive victories. Those of us among the 2,000 runners were ecstatic about the crowd reception and the news media attention. Insisting it could be bigger and better, Lebow had finally found his life’s work. He was the ideal person to put running on the map, a blend of high priest of our sport and P.ƒ|T. Barnum promoter — a man on a mission. Soon cities like Chicago, London and Berlin were sending emissaries to New York to learn how they might stage big urban marathons.

The race went off seamlessly, with Rodgers beating Shorter for the first of his four consecutive victories. Those of us among the 2,000 runners were ecstatic about the crowd reception and the news media attention. Insisting it could be bigger and better, Lebow had finally found his life’s work. He was the ideal person to put running on the map, a blend of high priest of our sport and P.ƒ|T. Barnum promoter — a man on a mission. Soon cities like Chicago, London and Berlin were sending emissaries to New York to learn how they might stage big urban marathons. As the popularity of the marathon increased, an entry became as hard to get as a reservation in one of the city’s hottest restaurants. Lebow relished telling stories about men who offered bribes and women who offered themselves to gain entry. He would drop comments like, “I had to turn down a request from Mayor Koch today.” In matters like this the truth could be stretched.

As the popularity of the marathon increased, an entry became as hard to get as a reservation in one of the city’s hottest restaurants. Lebow relished telling stories about men who offered bribes and women who offered themselves to gain entry. He would drop comments like, “I had to turn down a request from Mayor Koch today.” In matters like this the truth could be stretched. In 1990, Lebow received a diagnosis of brain cancer, which he accepted as just one more challenge. In the hospital, he began walking several miles each day in laps around the cancer ward. He calculated that 12 laps equaled a mile. After several months of treatments, with his cancer in remission, he began jogging everywhere as in the old days. When he announced that he planned to run the 1992 New York City Marathon, his dear friend and nine-time race winner, Grete Waitz, agreed to accompany him on the journey. Their long, slow run, which was cheered by millions of spectators, remains to this day the emotional high point of the race’s history.

In 1990, Lebow received a diagnosis of brain cancer, which he accepted as just one more challenge. In the hospital, he began walking several miles each day in laps around the cancer ward. He calculated that 12 laps equaled a mile. After several months of treatments, with his cancer in remission, he began jogging everywhere as in the old days. When he announced that he planned to run the 1992 New York City Marathon, his dear friend and nine-time race winner, Grete Waitz, agreed to accompany him on the journey. Their long, slow run, which was cheered by millions of spectators, remains to this day the emotional high point of the race’s history.